Grave of the Fireflies (1988), Isao Takahata

I wrote this essay in late 2019 for a unit in my History Honours degree at the University of Melbourne called “History, Memory, and Violence in Asia”. It was a brilliant subject, and I chose to produce a case study examining the firebombing of Kobe and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and how these events have been memorialised through the anime films of Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies. Both are two of my favourite films, and I consider them among the greatest war films ever made. They allow for a unique exploration of the horrors of war through the eyes of children, and move you on an elemental level with their pathos and emotion.

*

The children hunting

a cicada – not seeing

the Atom Bomb Dome

- Yasuhiko Shigemoto [1]

Introduction:

This case study examines the Allied atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the incendiary strategic bombing of Kobe as part of a broader campaign of aerial bombing against Japanese cities, civilians and military infrastructure between 1942-1945 in World War Two. The essay explores how anime as a medium of memory has afforded Japanese people a means with which to memorialise and historicise extreme wartime violence, to psychologically process the significant trauma of the bombings as both individuals and collective Japanese society, as well as to communicate particular messages about war and violence to subsequent generations in post-war Japan.

‘Anime’ is a popular and culturally significant form of animated media which originated in Japan, encompassing both hand-drawn and computer-generated animations.[2] From the early 20th century anime has both responded to and shaped mainstream film technologies and techniques. Its defining characteristics have been a combination of cinematography, fantasy, idealism, its unique stylization (i.e. emotive eyes and other expressive features), and a poetic appreciation of the Japanese understanding of the universal concept of mono no aware (物の哀れ), meaning pathos or a sensitivity to the ephemerality of life.[3] Though anime covers a range of different themes as a form of cultural expression, there is a defining or perennial focus on the theme of apocalypse and the destruction of human/Japanese society.[4]

These themes are particularly relevant to the two films I've selected for this essay: Barefoot Gen (1983) directed by Mori Masaki and Keiji Nakazawa, and Grave of the Fireflies (1988), directed by Isao Takahata. Through the perspectives of their child and teenage protagonists, the films examine the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the firebombing of Kobe, and their subsequent struggles for survival in Japanese society. Each of the historical events covered is apocalyptic in nature due to the unprecedented scale of the destruction of the bombings, and because of their unnatural and horrific consequences for humankind.[5] In considering the films, I analyse three common themes explored in each film through the medium of anime. Namely, how Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies interrogate the horror and violence of the respective bombings, how the memories and experiences of children in war are depicted, and the critiques of Japanese society during and after the war with a focus on poverty, malnutrition and hunger. I will also include a brief overview of how these anime representations have been received by sections of the Japanese community in the decades following their release.

Historical Context: The Incendiary Bombing of Kobe and the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

Strategic aerial bombing was part of an emerging mode of warfare developed in both European and Pacific theatres of conflict in World War II. It involved subjecting densely populated urban environments to sustained and intense aerial bombardments.[6] Such bombing resulted in mass civilian casualties, psychological terror, and severe destruction of residential, industrial and military buildings.[7] This type of warfare was practised by both Allied and Axis forces, and was variously labelled “terror bombing” by the Germans, “strategic bombing” by Americans, and “key area bombing” by the Japanese forces.[8]

Air-raids against the Japanese mainland began on 18 April 1942 in response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.[9] Led by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle, North American B-25 Mitchel bombers targeted highly populated and strategically important Japanese cities such as Kobe, Tokyo and Nagoya.[10] These aerial bombardments grew in lethality and horror as the Pacific War reached its crescendo in 1945, with the United States initiating a trial of the use of incendiary bombs in Japan to accelerate the end of the war.[11] The most devastating bombardment of Kobe occurred on 5 June 1945, in which 474 B-29 bombers incinerated and levelled 10km2 of the city centre, with 51% of Kobe’s urban surrounds damaged.[12] This particular attack provided the inspiration for the narrative events in Grave of the Fireflies. Between 1942 and 1945, the Allied aerial bombardments in Japan obliterated 466 square kilometres of the 67 cities targeted, killing over 300,000 people with another 400,000 injured.[13]

The protracted Allied strategic bombing campaign against Japan reached its destructive crescendo with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 respectively.[14] The atomic bombs instantly resulted in the deaths of over 66,000 and 30,000 at Hiroshima and Nagasaki respectively, with a study by Tadatoshi Akiba calculating that by 1950 over 200,000 in Hiroshima and over 140,000 in Nagasaki had died from the atomic bombs.[15] In the wake of the atomic bombings, the Imperial Japanese government and Emperor Hirohito acceded to the Potsdam Declaration.[16] This brought an end to almost fifteen years of conflict, beginning with the Manchurian Incident of 1931 to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The Japanese dead totalled three million soldiers and civilians.[17]

In the face of comprehensive and extensive documentation on by both the Allied and Japanese forces, there are no fundamental historiographical disputes about the general nature of the events nor the scale of the devastation caused and number of lives lost. Instead, the major sites of historical contestation have been whether strategic bombing of cities and the use of atomic bombs against civilian targets was necessary to fulfil the Allied military objectives; whether the bomb really ended the war; and to what extent the “collateral damage” of innocent civilian deaths was morally justifiable in achieving those strategic objectives.[18] A corollary to this is the debate about whether there is any moral difference between the use of conventional bombing and atomic bombing if the destructive impacts are broadly equivalent.[19]

Understanding Past Horrors: Anime and Memory Debates:

Following the Japanese government’s accession to the Potsdam Declaration, Japanese society was occupied by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) on 2 September 1945 as part of its unconditional surrender.[20] The American occupation of Japan lasted from 1945 until 1952. During this time, all Japanese artistic and cultural expression was tightly controlled by US authorities and education departments.[21] In particular, cultural depictions of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were strictly censored.[22] Such concealment and repression was intended to discourage any public unrest against the occupation, as well as to stymie any international momentum for a war-crimes trial against the United States equivalent to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.[23] The end of the occupation saw the unburdening of Japanese civil society, and with this came a gradual flourishing of art and cinema which gave expression to experiences of the atomic and incendiary bombings.[24] After the occupation ended, animated films in the style of manga and anime came to occupy a significant and popular place in shaping responses to the Japanese wartime experience.[25] Much of their cultural popularity and influence derived from the fact that manga and anime were readily available for both children and young adults, and that the subject material was not mediated by Japanese educational authorities.[26] It is instructive to view both Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies in these contexts.

As the progenitor behind the globally-popular Barefoot Gen - first in its manga form and then in the 1983 animated film - Keiji Nakazawa occupies a seminal place in Japanese and global memory and artistic culture.[27] In many interviews, Nakazawa has reflected widely on Barefoot Gen and its impact on understandings of the war and the use of atomic weaponry. In particular, Nakazawa has criticized the United States for eschewing responsibility for the use of atomic weapons, the self-destructive policies of Japan’s wartime leaders, and also the state of post-war Japanese politics.

Nakazawa experienced the Hiroshima bombing himself as a six year old boy, thereby rendering Barefoot Gen a semi-autobiographical work.[28] In a 2003 interview with Alan Gleason, Nakazawa noted that “I definitely based it [Barefoot Gen] on my own experiences growing up”.[29] There is therefore a nuanced dynamic at work between the expression of individual memory and the subsequent development of collective Japanese and global memory about the atomic bombings. Nakazawa notes that “’Barefoot Gen’ [in both its manga and anime formats] has been translated into more than 20 languages”.[30] This globalization of the memory is a significant feature of anime which speaks to its popularity and accessibility as a medium.[31]

Despite the overtly political nature of his commentary on Japanese politics in relation to the war, Nakazawa has consistently distanced himself from the anti-war political left, in particular the Japanese Communist Party.

Gleason: you’ve also mentioned before that the Japanese left wanted to use Gen for their own political agenda, and that at one point the Japanese Communist Party pestered you to join them.

Nakazawa: Oh yeah, sure, but I just said no. They left me alone after that.[32]

While disavowing the political left, Nakazawa is more explicit in his condemnation of the “ultra-nationalist” right.[33] Some scholars such as James Orr and Christine Hong have suggested that Barefoot Gen the film – which emphasises the suffering of the Japanese people and does not include portrayals of Japanese war crimes like the manga version – could be seen as sympathetic to the conservative narrative of victimization advocated by some mainline Japanese politicians, such as “militarists” within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.[34] Nakazawa’s response below does much to dispel that assertion through its revelation of his attitudes to Japan’s wartime leadership, the dangerous revisionism of Japan’s post-war polity, and his strong criticism of the imperial system.

Nakazawa: Japan is just as bad. Here’s a country that experienced complete devastation in the last war, and yet ultra-nationalists are crawling out of the woodwork again, glorifying the war and trying to rewrite the history textbooks. And as usual they talk about restoring the emperor to his rightful position of absolute authority. [35]

Similar to how Nakazawa’s lived experience of the atom bomb in Hiroshima informed the creation of Barefoot Gen, director and animator Isao Takahata experienced the aerial firebombing in his hometown Okayama, which may have informed the realism of the visual production.[36] When faced with the question about how to convert such individual experience into a visual reproduction or memorialization, Takahata identified anime as the most effective medium to elicit emotional responses in the audience, as it more easily allowed creators to “convey visual expressions, express emotions, feelings that you’d never be able to reach with actors”.[37] This reflection supports the thesis that anime can depict images of the past with greater ease than film or photography, since it is beyond the norms and technical restrictions of realism.[38]

Grave of the Fireflies is conventionally viewed as an anti-war film. However, in an interview with Anime News Network, Takahata refuted this characterisation, suggesting that the film was more an expression of human tragedy rather than an overt or effective political statement which could prevent war.[39] While unwilling to situate Grave of the Fireflies within broader anti-war efforts, in the same interview Takahata was highly critical of conservative Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his determination to revise Article 9 of the Constitution, which proscribes Japan from engaging in armed conflict to settle international disputes.[40]

Remembrance of Things Past: Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies:

Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies memorialise related historical events of atomic and strategic aerial bombing through the medium of anime. This section of the case study will examine three common themes between the films and examine their stylistic approaches at rendering meaning and memory for the audience, including depictions of aerial bombings and the subsequent horror, the memories, perspectives, and experiences of children during war, and reflections on Japanese society during and after the war.

Depictions of aerial bombings and subsequent horror:

The depiction of the air raid in Kobe begins with the terror and chaos of a claustrophobic streetscape. From an unsettling first-person camera angle, the audience follows protagonists Seita (a young teenager) and his little sister Setsuko (four years old) through the winding streets of Kobe as incendiary bombs are rain down from above. The wailing sirens interweave with the cries of children, adding a terrifying element of historical realism to the scene. In Figure 2, the audience are presented with a panning landscape shot from a beach on Osaka bay demonstrating the full scale of destruction wrought by the air raid over Kobe. Tens of B-29 bombers slowly strafe the city which is now unrecognisable and entirely consumed by fire.

Barefoot Gen approaches the depiction of the bombing in a markedly different manner. Rather than the buzzing and frenetic chaos of the squadron of bombers descending on the city, there is an ominous absence of dialogue combined with sparse drumbeats and slowly ascending piano notes. The Enola Gay makes its way over Hiroshima unmet by air raid sirens, until the singular, cataclysmic atomic bomb is dropped and witnessed in all its destruction from a panoptical perspective (Figure 4). Scholars have emphasised the different style in which the pilots aboard the Enola Gay (Figure 3) are depicted compared with the other characters in Barefoot Gen.[45] This stylistic decision highlights the inhuman nature of the enemy and their atomic weapons.

Figure 5 (Grave, 19:22)[46] Figure 6 (Barefoot Gen, 35:44)[47]

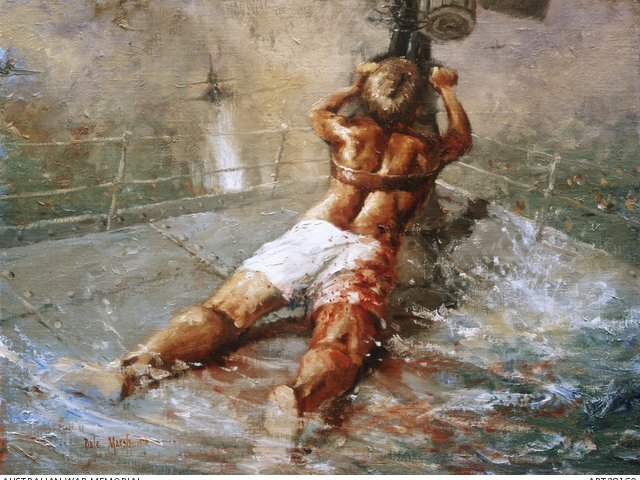

The horrific effects of the firebombing of Kobe and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima are detailed in Figures 5 and 6 respectively. Barefoot Gen’s Figure 6 is reminiscent of Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi’s The Hiroshima Panels, completed between 1950-1982. The image is one of pure horror: an emaciated, zombie-like mother and her infant child stumble through the smoke of the obliterated city with their skin melting and dripping from their limbs, eyeballs hanging from their sockets, and shards of glass and shrapnel piercing their skin. This visual description is not one borne of fantasy. It recalls and supports many testimonials from survivors of the Hiroshima bombing.[48] Similarly, Figure 5 depicts Seita and Setsuko’s mother bandaged up and burnt beyond shortly before her death. The anonymity in her severely burnt state emphasises the dehumanizing nature of the violence perpetrated against citizens by the Allied forces.[49] Various close ups reveal the full extent of the mutilation, with her skin entirely seared away as she lies in an unhygienic makeshift hospital, beset by flies and maggots. This is an accurate representation of the effects of Allied incendiary bombing against Japanese cities and the incapacity of the Japanese healthcare system to cope with the unprecedented destruction and human collateral damage.[50]

Figure 7 (Gen, 44:31)[51] Figure 8 (Grave, 11:27)[52]

The memories, perspectives and experiences of children in wartime:

Both Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies explore the experience of wartime Japan through the perspective of children, capturing both their playful freedom and suffering as civil society broke down.[53] This is a recurring motif of anime films, and it allows directors to channel the innocence of children to contrast and interrogate the evil and incomprehensibility of the adult world. Figure 7 depicts Gen in the aftermath of the atomic bomb, having just prepared a shelter for his mother and the recently born Tomoko. Suddenly, black rain starts falling from the sky, prompting Gen to ask: “mother, have you ever seen rain that’s black like this?” A narrative voice appears outside of the diegetic world of the film, which importantly provides an educative aside to the audience which the anime characters themselves are not privy to:

the black rain began falling on the northwest section of the city, the impact of the bomb’s blast had sent dust, debris and radiation high into the atmosphere where it gathered in a gigantic, lethal cloud. Before returning to the earth as radioactive rain. The bomb that fell on the city detonated with a destructive force of 20,0000 tons of TNT and generated temperatures in excess of 4,000 degrees Celsius. Some 60% of the city had vanished but the damage did not end there. The people of Hiroshima did not know it yet, but the bomb’s aftereffects, such as the black rain, would bring them many years of suffering.[54]

A parallel scene with black rain occurs in Grave of the Fireflies in Figure 8, with both Seita and Setsuko greeting the rain with childlike curiosity and interest. Deprived of the atomic dimension, the inclusion of black rain after the incendiary bombing emphasises the unnaturalness of war and the totality of the destruction wrought on Kobe, rather than the otherworldly and unfathomable horror of Hiroshima.[55] The black rain that fell and the “many years of suffering” referred to by the narrative voice is indicative of the high rates of cancer and radiation-related illnesses experienced by the 650,000 survivors of the atomic bombs.[56]

Figure 9 (Barefoot Gen, 1:13:50)[57] Figure 10 (Grave, 1:19:05)[58]

Reflections on Japanese society during and after the war:

Children suffering from malnutrition and poverty was common in wartime.[59] In Figure 9, the triumphant Gen and Ryuta (the adopted orphan and new brother to Gen) have just returned from their playful adventure to earn money and buy food for their family. They discover that the newborn Tomoko has recently perished from malnutrition and are greeted by the shocking image of a withered and pockmarked infant swaddled in her grieving mother’s arms. Similarly, in Figure 10 Seita returns from procuring money and resources in a nearby city only to find Setsuko in a state of delirium – eating marbles and dirt in lieu of food - and on the brink of death. It’s difficult to imagine which images in cinema could exude more pathos than these. Having survived the devastation of incendiary aerial bombardment and an atomic bomb, these youthful innocents succumb to malnutrition and disease, an often unspoken and underrepresented horror of war which does not discriminate between soldier and civilian. Tomoko, Ryuta and Setsuko are representative of the estimated 123,000 children either orphaned or rendered homeless by 1948, many of whom endured poverty, malnourishment and loneliness in the months and years preceding their deaths.[60]

Contested/sensitive representations:

The anime version of Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies have not caused particularly heated or contested debates on the scale of the Japanese History Textbook Controversies of the 1980s and beyond. This is especially true of Grave of the Fireflies. However, as alluded to earlier in this essay, there have been certain instances in which the Barefoot Gen has irritated both the left and right sides of Japanese political/historiographical spectrum.

One recent example of this is the Association of Atomic Bomb Victims for Peace and Security campaigning for the Hiroshima City Board of Education to remove Barefoot Gen – both as manga and anime film - from educational settings, due to the “opinion and ideology” of Keiji Nakazawa.[61] As mentioned earlier in this essay, Nakazawa is a strident pacifist and highly critical of both wartime Japan and the imperial system. The Hiroshima City Board of Education uses Barefoot Gen in manga and film to develop historical empathy in primary school students as part of its peace studies programs. The Association does not include any direct victims of the 1945 bombing, and is largely thought to be a neo-nationalist, revisionist movement which seeks to remove anti-nuclear literature and advocate for the nuclear armament of Japan as well as a conventional remilitarization of the Japanese armed forces.[62] Similarly, following Nakazawa’s death in December 2012, the board of education in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture limited access to Barefoot Gen because of its anti-war message and because of the graphic nature of the violence depicted as perpetrated by Japanese soldiers.[63]

The anime adaptation of Barefoot Gen has also generated a critical reaction from those on the political and historiographical left, which is overtly anti-war in its posture and remains critical and realistic about the Imperial Japanese wartime record. The film omits much of the criticism of the Japanese government that was central to the manga version of Barefoot Gen, its alien depiction of the pilots of the Enola Gay does not indicate that the enemy was provoked by Japanese militarism, and depicts the obliteration of Hiroshima and the defeat of Japan as tragedy rather than the consequence of the Imperial Japanese war machine’s trail of destruction since 1931.[64] Therefore the critical suggestion is that the film, as opposed to the print version of Barefoot Gen, comfortably fits within the conservative, nationalist narrative of victimization, and could be considered similar to other revisionist wartime anime films such as The Wind Rises.

Conclusion:

This case study has considered the historical events of the firebombing of Kobe and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and how these events have been memorialised through the anime films of Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies. It has explored how anime has mediated Japanese responses to the violence of wartime atrocities. Through its popularity as a genre, both Barefoot Gen and Grave of the Fireflies have allowed historical understandings of the Japanese experience of war to be communicated to subsequent generations. The common themes focused on how horror and violence were portrayed, how the experiences of children are represented and understood, and critiques of post-war Japanese society and its imposition of structural violence or suffering on its citizenry.

***

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

AnimeForLife. “Grave of the Fireflies Full Movie English Sub”. YouTube video, 1:26:34, 12 June 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vldWhL5JQxg&t=514s

Chakra. “Watch Barefoot Gen Full Movie English Sub 1080p HD”. YouTube video, 1:26:10, 30 September 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqDQd1wkDj0

Masaki, Mori, Toshio Hirata, Kentarō Haneda, and Keiji Nakazawa. 1983. Barefoot Gen.

Gleason, Alan. “Keiji Nakazawa Interview”, The Comics Journal http://www.tcj.com/keiji-nakazawa-interview/ (accessed 30 November 2019)

Rie Nii, “My Life: Interview with Keiji Nakazawa, Author of “Barefoot Gen,” Part 14”, available at http://www.hiroshimapeacemedia.jp/?p=24184

Asai Motoofumi, translated by Richard H. Minear, “Barefoot Gen, The Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima legacy”, 1 January 2008, https://apjjf.org/-Nakazawa-Keiji/2638/article.html

Nakazawa Keiji and Richard H. Minear, "Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen," The Asia-Pacific Journal, 39-1-10, September 27, 2010.

Keiji, Nakazawa. Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010. - https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/reader.action?docID=634319

Littardi, Cedric. “An Interview with Isao Takahata”, AnimeLand. http://www.nausicaa.net/miyazaki/interviews/t_corbeil.html (accessed 29 November 2019)

Eric Stimson, “Isao Takahata Offers His Thoughts on war, Constitution”, https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interest/2015-02-26/isao-takahata-offers-his-thoughts-on-war-constitution/.85346, 27 February 2015

Takahata, Isao, and Akiyuki Nosaka. 1988. Grave of the fireflies.

Websites/News Articles:

DeHart, Jonathan, “Barefoot Gen: Manga, History and Japan’s Right-Wing Fringe”, The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2013/08/barefoot-gen-manga-history-and-japans-right-wing-fringe/ (accessed 2 December 2019).

Fuller, Frank. “The deep influence of the A-bomb on anime and manga”. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/the-deep-influence-of-the-a-bomb-on-anime-and-manga-45275 (accessed 30 November 2019).

McNeill, David. “Hiroshima Haiku: Expressing horror in 17 syllables”. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/asia-pacific/hiroshima-haiku-expressing-horror-in-17-syllables-1.2663898 (accessed 6 December 2019)

Selden, Mark. “American Fire Bombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory”. The Asia-Pacific Journal. https://apjjf.org/2016/23/Selden.html (accessed 10 December 2019)

Penney, Matthew. “Neo-nationalists Target Barefoot Gen.” The Asia-Pacific Journal. https://apjjf.org/-Matthew-Penney/4733/article.html (accessed 10 December 2019).

Books:

Berry, Michael, and Chiho Sawada. 2016. Divided lenses: screen memories of war in East Asia. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1222613.

Broderick, Mick. 2013. Hibakusha cinema: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the nuclear image in Japanese film. https://nls.ldls.org.uk/welcome.html?ark:/81055/vdc_100025763699.0x000001.

Burchett, Wilfred. 1983. Shadows of Hiroshima. London: Verso.

Chapman, Jane L., Dan Ellin, and Adam Sherif. 2015. "Barefoot Gen and Hiroshima: Comic Strip Narratives of Trauma".

Clapson, Mark. 2019. The Blitz Companion. University of Westminster.

Conway-Lanz, Sahr. 2013. Collateral Damage Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity after World War II. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

Craig, Timothy J. 2015. Japan pop!: inside the world of Japanese popular culture. http://site.ebrary.com/id/11042487.

Dower, John W. 2000. Embracing defeat: Japan in the wake of World War II. London: Penguin.

Hersey, John. 1946. Hiroshima. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Jacobs, Robert, Mick Broderick, and Robert A. Jacobs. 2010. Filling the Hole in the Nuclear Future. Lanham: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

Kim, Mikyoung. 2019. Routledge handbook of memory and reconciliation in East Asia

Lifschultz, Lawrence, and Kai Bird. 1998. Hiroshimaʼs shadow: [writings on the denial of history and the Smithsonian controversy]. Stony Creek (CT): Pamphleeter's Press.

Lowenstein, Adam. 2015. Dreaming of cinema: spectatorship, surrealism, and the age of digital media. New York: Columbia Univ. Press.

Ma, Sheng-mei. 2007. East-West montage: reflections on Asian bodies in diaspora. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Minnear, Richard H. 2018. Hiroshima: Three Witnesses. https://www.degruyter.com/doi/book/10.23943/9780691187259.

Miyamoto, Yuki. 2012. Beyond the mushroom cloud: commemoration, religion, and responsibility after Hiroshima. New York: Fordham University Press.

Nagai, Takashi, and William Johnston. 2002. The bells of Nagasaki. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Shapiro, Jerome F. 2013. Atomic Bomb Cinema. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=1195834.

Tanaka, Yuki, and Marilyn B. Young. 2010. Bombing Civilians: a Twentieth-Century History. New York: New Press. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=584787.

Zwigenberg, Ran. 2016. Hiroshima: the origins of global memory culture.

Journal Articles:

Akimoto, Daisuke. 2014. Peace education through the animated film “Grave of the Fireflies” physical, psychological, and structural violence of war. http://jairo.nii.ac.jp/0026/00006560.

Alt, Joachim. "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Feature Length Animation Movies." In The 11th Convention of the International Association for Japan Studies. 2015.

Berndt, Jaqueline. "Facing the Nuclear Issue in a “Mangaesque” Way: The Barefoot Gen Anime." Cinergie–Il Cinema e le altre Arti 1, no. 2 (2012): 148-162.

CAMERON, LINDSLEY, and MASAO MIYOSHI. 2005. "HIROSHIMA, NAGASAKI, and the World Sixty Years Later". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 81 (4): 26-47.

Delamothe, Tony. 1989. "Hiroshima: The Unforgettable Fire". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 299 (6706): 1023-1025.

Dower, John W. 1995. "The Bombed: Hiroshimas and Nagasakis in Japanese Memory". Diplomatic History. 19 (2): 275.

Feleppa, Robert. 2004. "BLACK RAIN: Reflections on Hiroshima and Nuclear War in Japanese Film". CrossCurrents. 54 (1): 106-119.

Goldberg, Wendy. 2009. "Transcending the Victim's History: Takahata Isao's "Grave of the Fireflies". Mechademia. 4: 39-52.

Hashimoto, Akiko. "Something Dreadful Happened in the Past': War Stories for Children in Japanese Popular Culture." The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 13 (2015): 30.

Hong, Christine. "Flashforward democracy: American exceptionalism and the atomic bomb in Barefoot Gen." Comparative Literature Studies 46, no. 1 (2009): 125-155.

Ichitani, T. 2010. "Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms: The Renarrativation of Hiroshima Memories". JNT -YPSILANTI MI-. 40: 364-390.

International Conference of the EAJS (European Association for Japanese Studies), Sven Saaler, and Wolfgang Schwentker. 2008. The power of memory in modern Japan. Folkestone, UK: Global Oriental. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9781905246380.i-382.

Jones O. 2012. "Black rain and fireflies: The otherness of childhood as a non-colonising adult ideology". Geography. 97 (3): 141-146.

Katzenstein, P. J., and Takashi Shiraishi. 1997. Network power: Japan in Asia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kawaguchi, Takayuki. "Barefoot Gen and “A-bomb literature”: re-recollecting the nuclear experience." (2010).

Kim, Mikyoung. 2008. "Pacifism or Peace Movement?: Hiroshima Memory Debates and Political Compromises". Journal of International and Area Studies. 15 (1): 61-78.

Lisa Yoneyama, "On Testimonial Practices", in Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space and the Dialectics of Memory (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), pp. 85-111.

Konaka, Yōtarō, and Winifred Olsen. 1988. "Japanese Atomic-Bomb Literature". World Literature Today. 62 (3): 420-424.

Ma, Sheng-mei. 2007. East-West montage: reflections on Asian bodies in diaspora. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Ma, Sheng-mei. 2010. "Three Views of the Rising Sun, Obliquely: Keiji Nakazawa's A-bomb, Osamu Tezuka's Adolf, and Yoshinori Kobayashi's Apologia". Mechademia. 4 (1): 183-196.

Maier, Charles S. 2005. "Targeting the City: Debates and Silences about the Aerial Bombing of World War II". International Review of the Red Cross. 87 (859): 429-444.

Joachim Alt. “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Feature

Length Animation Movies”. The International Association for Japan Studies, 12 December 2015, Toyo University

Miyamoto, Yuki. 2012. Beyond the mushroom cloud: commemoration, religion, and responsibility after Hiroshima. New York: Fordham University Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10539015.

Nakazawa, Keiji, and Art Spiegelman. Barefoot Gen: The Day After. Vol. 2. Last Gasp, 2004.

Napier, Susan J. 2016. Anime from akira to howl's moving castle: experiencing contemporary Japanese animation. New York: St. Martin's Press. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=D329E888-F2E4-4E0F-877E-5ECBEB46785A.

Napier, Susan J. "No More Words: Barefoot Gen, Grave of the Fireflies, and “Victim’s History”." In Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke, pp. 161-173. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2001.

John Nelson, "Social Memory as Ritual Practice: Commemorating Spirits of the Military Dead at Yasukuni Shinto Shrine," Journal of Asian Studies 62, 2 (2003), pp. 445-467.

Norihito, Mizuno. "The Dispute over Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen) and Its Implications in Japan." International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 5, no. 11 (2015): 955.

Schaefer, Stefanie, ‘The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and its Exhibition’, in The Power of Memory in Modern Japan, ed. Sven Saaler and Wolfgang Schwentker, Global Oriental, Folkestone, 2008, pp. 155-170.

Silberner, Joanne. 1981. "Psychological A-Bomb Wounds". Science News. 120 (19): 296.

Swale, Alistair. 2017. "Memory and forgetting: examining the treatment of traumatic historical memory in Grave of the Fireflies and The Wind Rises". Japan Forum. 29 (4): 518-536.

Szasz F.M., and Takechi I. 2007. "Atomic heroes and atomic monsters: American and Japanese cartoonists confront the onset of the nuclear age, 1945-80". Historian. 69 (4): 728-752.

Ichitani, Tomoko. "Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms: The Renarrativation of Hiroshima Memories." Journal of Narrative Theory 40, no. 3 (2010): 364-390.

Stahl, D. Imag(in)ing the War in Japan [electronic resource] : Representing and Responding to Trauma in Postwar Literature and Film. Leiden : BRILL, 2010.

Stahl, David C. n.d. "Victimization And "Response-Ability": Remembering, Representing, And Working Through Trauma In Grave Of The Fireflies". 161-202.

Endnotes:

[1] David McNeill, “Hiroshima Haiku: Expressing horror in 17 syllables”. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/asia-pacific/hiroshima-haiku-expressing-horror-in-17-syllables-1.2663898 (accessed 6 December 2019)

[2] Frank Fuller, “The deep influence of the A-bomb on anime and manga”. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/the-deep-influence-of-the-a-bomb-on-anime-and-manga-45275 (accessed 30 November 2019).

[3] Timothy J. Craig., 2015. Japan pop!: inside the world of Japanese popular culture. http://site.ebrary.com/id/11042487. p 138

[4] Susan J. Napier. Anime from Akira to Howl's Moving Castle: experiencing contemporary Japanese animation. New York: St. Martin's Press. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=D329E888-F2E4-4E0F-877E-5ECBEB46785A. p 249

[5] Jane L Chapman, Dan Ellin, and Adam Sherif. 2015. "Barefoot Gen and Hiroshima: Comic Strip Narratives of Trauma" pp 51

[6] Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn B. Young. 2010. Bombing Civilians: a Twentieth-Century History. New York: New Press. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=584787.

[pp, 138-9]

[7] Mark Selden. “American Fire Bombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory”. The Asia-Pacific Journal. https://apjjf.org/2016/23/Selden.html (accessed 10 December 2019).

[8] Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn B. Young. 2010. Bombing Civilians: a Twentieth-Century History. New York: New Press. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=584787. P 139

[9] Lawrence Lifschultz, and Kai Bird. 1998. Hiroshimaʼs shadow: [writings on the denial of history and the Smithsonian controversy]. Stony Creek (CT): Pamphleeter's Press. P 55

[10] Mark Selden. “American Fire Bombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory”. The Asia-Pacific Journal. https://apjjf.org/2016/23/Selden.html (accessed 10 December 2019).

[11] Lawrence Lifschultz, and Kai Bird. 1998. Hiroshimaʼs shadow: [writings on the denial of history and the Smithsonian controversy]. Stony Creek (CT): Pamphleeter's Press. P 51

[12] Daisuke Akimoto, 2014. Peace education through the animated film “Grave of the Fireflies” physical, psychological, and structural violence of war. http://jairo.nii.ac.jp/0026/00006560. P 36

Sahr Conway-Lanz, 2013. Collateral Damage Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity after World War II. Florence: Taylor and Francis, Bottom of Formp 1

[14] John W. Dower, 2000. Embracing defeat: Japan in the wake of World War II. London: Penguin [p 415]

[15] Lindsley Cameron, and Masao Miyoshi. 2005. "HIROSHIMA, NAGASAKI, and the World Sixty Years Later". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 81 (4): 26-47., P 28-29

[16] Lawrence Lifschultz, and Kai Bird. 1998. Hiroshimaʼs shadow: [writings on the denial of history and the Smithsonian controversy]. Stony Creek (CT): Pamphleeter's Press. pp 41-45

[17] John W. Dower, 1995. "The Bombed: Hiroshimas and Nagasakis in Japanese Memory". Diplomatic History. 19 (2): 275 [pp 218-219]

[18] Maier, Charles S. 2005. "Targeting the City: Debates and Silences about the Aerial Bombing of World War lII". International Review of the Red Cross. 87 (859): 429-444; Lawrence Lifschultz, and Kai Bird. 1998. Hiroshimaʼs shadow: [writings on the denial of history and the Smithsonian controversy]. Stony Creek (CT): Pamphleeter's Press. P 49050

[19] Lawrence Lifschultz, and Kai Bird. 1998. Hiroshimaʼs shadow: [writings on the denial of history and the Smithsonian controversy]. Stony Creek (CT): Pamphleeter's Press. pp xviii-xix

[20] Joachim Alt, "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Feature Length Animation Movies." In The 11th Convention of the International Association for Japan Studies. 2015. P 3-4

[21] Mikyoung Kim, 2019. Routledge handbook of memory and reconciliation in East Asia. P. 6; Kim, Mikyoung. 2008. "Pacifism or Peace Movement?: Hiroshima Memory Debates and Political Compromises". Journal of International and Area Studies. 15 (1): 61-78. Pp 64-66

[22] Mick Broderick. 2013. Hibakusha cinema: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the nuclear image in Japanese film. https://nls.ldls.org.uk/welcome.html?ark:/81055/vdc_100025763699.0x000001. P 103; Mikyoung Kim. 2008. "Pacifism or Peace Movement?: Hiroshima Memory Debates and Political Compromises". Journal of International and Area Studies. 15 (1): 61-78. Pp 65-66

[23] John W. Dower. 1995. "The Bombed: Hiroshimas and Nagasakis in Japanese Memory". Diplomatic History. 19 (2): p 275-276

[24] Jerome F. Shapiro, 2013. Atomic Bomb Cinema. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=1195834. P 53

[25] Alistair Swale 2017. "Memory and forgetting: examining the treatment of traumatic historical memory in Grave of the Fireflies and The Wind Rises". Japan Forum. 29 (4): 518-536. p. 518

[26] Akiko Hashimoto. "Something Dreadful Happened in the Past': War Stories for Children in Japanese Popular Culture." The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 13 (2015): 1

[27] Asai Motoofumi, translated by Richard H. Minear, “Barefoot Gen, The Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima legacy”, 1 January 2008, https://apjjf.org/-Nakazawa-Keiji/2638/article.html

[28] Jane L Chapman, Dan Ellin, and Adam Sherif. 2015. "Barefoot Gen and Hiroshima: Comic Strip Narratives of Trauma". P 50

[29] Alan Gleason. “Keiji Nakazawa Interview”, The Comics Journal http://www.tcj.com/keiji-nakazawa-interview/ (accessed 30 November 2019)

[30] Rie Nii, “My Life: Interview with Keiji Nakazawa, Author of “Barefoot Gen,” Part 14, available at http://www.hiroshimapeacemedia.jp/?p=24184

[31] Adam Lowenstein, 2015. Dreaming of cinema: spectatorship, surrealism, and the age of digital media. New York: Columbia Univ. Press. P 79

[32] Alan Gleason,. “Keiji Nakazawa Interview”, The Comics Journal http://www.tcj.com/keiji-nakazawa-interview/ (accessed 30 November 2019)

[33] Ibid

[34] Christine Hong. "Flashforward democracy: American exceptionalism and the atomic bomb in Barefoot Gen." Comparative Literature Studies 46, no. 1 (2009): 125-155. P 138

[35] Alan Gleason, “Keiji Nakazawa Interview”, The Comics Journal http://www.tcj.com/keiji-nakazawa-interview/ (accessed 30 November 2019)

[36] David C Stahl,. n.d. "Victimization And "Response-Ability": Remembering, Representing, And Working Through Trauma In Grave Of The Fireflies". 161-202. P 164

[37] Cedric Littardi. “An Interview with Isao Takahata”, AnimeLand. http://www.nausicaa.net/miyazaki/interviews/t_corbeil.html (accessed 29 November 2019)

[38] T Ichitani 2010. "Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms: The Renarrativation of Hiroshima Memories". P 368

[39] Eric Stimson, “Isao Takahata Offers His Thoughts on war, Constitution”, https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interest/2015-02-26/isao-takahata-offers-his-thoughts-on-war-constitution/.85346, 27 February 2015

[40] Eric Stimson, “Isao Takahata Offers His Thoughts on war, Constitution”, https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interest/2015-02-26/isao-takahata-offers-his-thoughts-on-war-constitution/.85346, 27 February 2015

[41] AnimeForLife. “Grave of the Fireflies Full Movie English Sub”. YouTube video, 1:26:34, 12 June 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vldWhL5JQxg&t=514s , at 08:21

[42] Ibid at 08:58

[43] Chakra. “Watch Barefoot Gen Full Movie English Sub 1080p HD”. YouTube video, 1:26:10, 30 September 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqDQd1wkDj0 at 31:28

[44] Ibid at 34:37

[45] Joachim Alt, "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Feature Length Animation Movies." In The 11th Convention of the International Association for Japan Studies. 2015, 5-6

[46] AnimeForLife. “Grave of the Fireflies Full Movie English Sub”. YouTube video, 1:26:34, 12 June 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vldWhL5JQxg&t=514s at 19:22

[47] Chakra. “Watch Barefoot Gen Full Movie English Sub 1080p HD”. YouTube video, 1:26:10, 30 September 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqDQd1wkDj0 at 35:44

[48] Jane L. Chapman, Dan Ellin and Adam Sherif, 2015. "Barefoot Gen and Hiroshima: Comic Strip Narratives of Trauma"; John Hersey 1946. Hiroshima. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp 50-51

[49] Burchett, Wilfred. 1983. Shadows of Hiroshima. London: Verso. P 37

[50] Silberner, Joanne. 1981. "Psychological A-Bomb Wounds". Science News. 120 (19): 296, p 297, Tony Delamothe. 1989. "Hiroshima: The Unforgettable Fire". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 299 (6706): 1023-1025. P 1024

[51] Chakra. “Watch Barefoot Gen Full Movie English Sub 1080p HD”. YouTube video, 1:26:10, 30 September 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqDQd1wkDj0 at 44:31

[52] AnimeForLife. “Grave of the Fireflies Full Movie English Sub”. YouTube video, 1:26:34, 12 June 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vldWhL5JQxg&t=514s at 11:27

[53] Jones O. 2012. "Black rain and fireflies: The otherness of childhood as a non-colonising adult ideology". Geography. 97 (3): 141-146. P 144-5

[54] Chakra. “Watch Barefoot Gen Full Movie English Sub 1080p HD”. YouTube video, 1:26:10, 30 September 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqDQd1wkDj0 at 00:44:32

[55] Jones O. 2012. "Black rain and fireflies: The otherness of childhood as a non-colonising adult ideology". Geography. 97 (3): 141-146. P 145

[56] Tony Delamothe,. 1989. "Hiroshima: The Unforgettable Fire". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 299 (6706): 1023-1025. P 1023

[57] Chakra. “Watch Barefoot Gen Full Movie English Sub 1080p HD”. YouTube video, 1:26:10, 30 September 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqDQd1wkDj0 at 1:13:50

[58] AnimeForLife. “Grave of the Fireflies Full Movie English Sub”. YouTube video, 1:26:34, 12 June 2018. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vldWhL5JQxg&t=514s at 1:19:05

[59] Wendy Goldberg, 2009. "Transcending the Victim's History: Takahata Isao's "Grave of the Fireflies". Mechademia. 4: 39-52. P 40-42

[60] Jerome Shapiro., "Ninety Minutes over Tokyo: Aesthetics, Narrative, and Ideology in Three Japanese Films about the Air War". 375-394, p 383

[61] Matthew Penney, “Neo-nationalists Target Barefoot Gen.” The Asia-Pacific Journal. https://apjjf.org/-Matthew-Penney/4733/article.html (accessed 10 December 2019).

[62] Matthew Penney, “Neo-nationalists Target Barefoot Gen.” The Asia-Pacific Journal. https://apjjf.org/-Matthew-Penney/4733/article.html (accessed 10 December 2019).

[63] Jonathan DeHart, “Barefoot Gen: Manga, History and Japan’s Right-Wing Fringe”, The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2013/08/barefoot-gen-manga-history-and-japans-right-wing-fringe/ (accessed 2 December 2019).

[64] Joachim Alt, "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Feature Length Animation Movies." In The 11th Convention of the International Association for Japan Studies. 2015. p 6