I recently found the below essay on my laptop while clearing out old material. It was a “SAC” (School-Assessed Coursework) for a Philosophy unit in the Victorian Certificate of Education, written in Melbourne, Australia in 2010.

The task was to write a letter to your unborn child, drawing on philosophical concepts from the course. The course was concerned with the good life, and living well. It was taught by the wonderful Dr Felicity McCutcheon, one of the best teachers I’ve ever had, and more importantly one of the kindest and wisest souls I’ve ever met. The letter, at nearly 1800 words, grapples with the philosophy of Plato, Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer, applying it to the 21st century. There’s a lot in the letter I would change and temper with age and experience, especially the prose, but I’ve found the hopefulness and life-affirming tone of the letter to be really refreshing.

It’s remarkable to read something I wrote 14 years ago, especially at such a young age. It’s almost as if it were written by a stranger. At 32 years old now, I am indeed a completely different person. So much has happened since - I’ve lived all over the world, attended university, worked in meaningful and interesting jobs. I’ve fallen in love, made friends, and seen places that have made me feel truly alive. I hope 18 year old me would have been proud of who I have become, and am becoming. The road certainly hasn’t been easy, there has been a lot of pain and disappointment and failure along the way. I suppose this is the same for everyone. It has given me a lot of strength to re-read this letter (at a time when I really need it), and to think of the hopefulness and intellectual curiosity of my younger self, so filled with possibility, and to think of the quiet bravery of how I tried to make the most out my one little life at that age. The letter ultimately calls for a spirit of exploration, creativity, transcendence, seeking something more, and connectedness with others.

The idea of having a child still seems far away, though not as much as when I was 18. Many of my friends and peers are settling down with long term partners, making homes of their own, and welcoming children into the world. I hope all of this happens for me, and that I can be a loving and caring father and husband.

***

Written July, 2010

a) Write a letter to your unborn child, advising them on the best way to live (with reference to 21st century).

To my unborn,

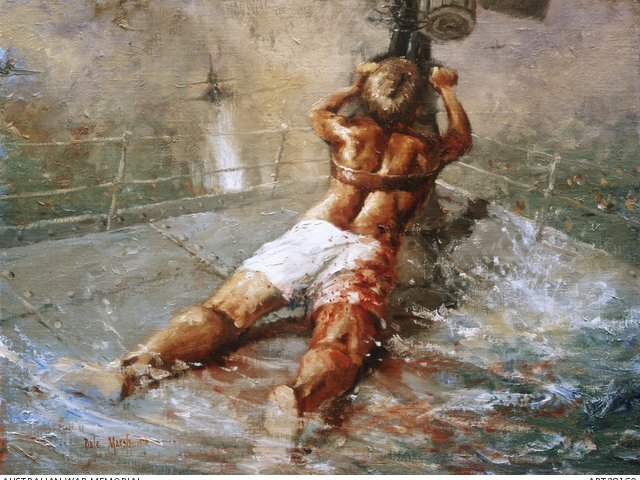

Perhaps it is fitting that I am writing this letter to you as you unknowingly prepare to be cast from the darkness of your metaphorical cave and into the light of the world. The nature of this letter is one advocating a life of discovery, of transcendence from the darkness to the light, and of leaving obscurity for the dual truth of your existence, if you are so willing. I do not pretend that this life will be an easy one; it will be challenging and uncomfortable. However, the authenticity and satisfaction derived from embracing your humanity and striving for some higher goal, even if it is never attained, will allow you to arrive at a truth of our existence that is greater in depth and dimension than would be able to be obtained if the ‘truth’ of your perceived circumstances was simply accepted and permitted by your indifference to shaping your life.

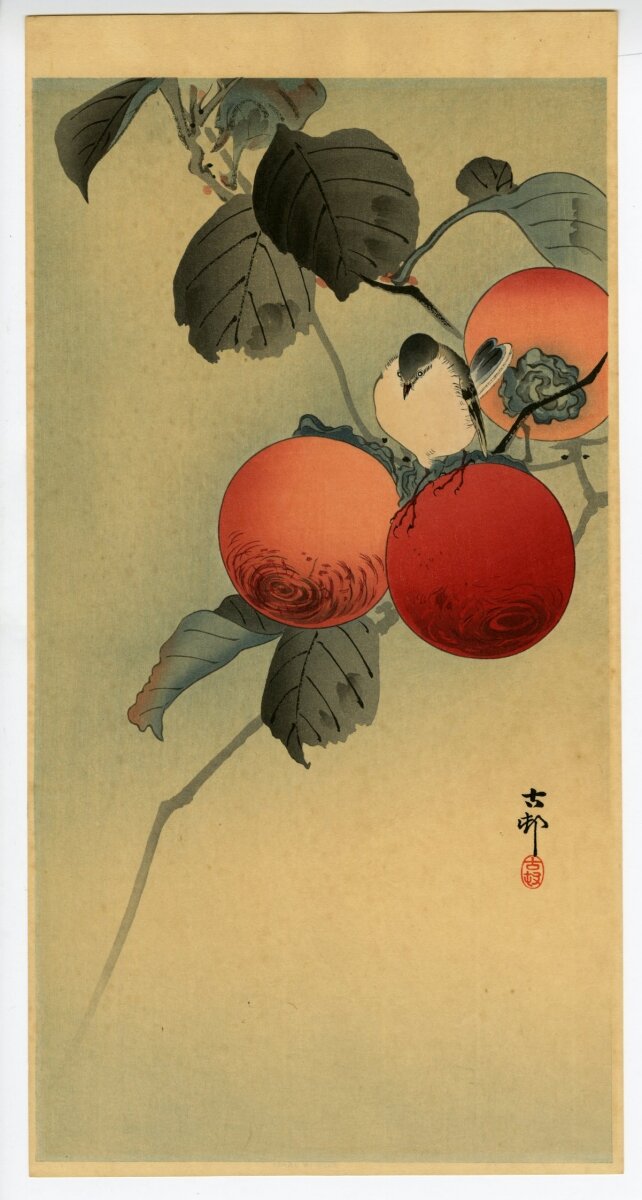

What merit is there in sourcing and embracing this alluded to eternal propulsion towards something more? I cannot for me say with any tangible validation what exactly this drive is, I can only infer that it exists, and it is innate in every human. It is the desire, drive, impulse, the urge to break out of comfortability in the pursuit of that more. It was the humans who left the Rift Valley all those thousands of years ago, it was man reaching out, however ineffectually, to the depths of space, and it is man searching for his soul mate. Here is an excerpt from Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid:

“Stabant orantes primi transmittere cursum

Tendebantque manus ripae ulterioris amore”“So they all stood, each praying to be ferried across first

Their hands stretched out in longing for the further shore”

It is my belief that it is this endeavour, combined with the perseverance and honesty to commit to these chosen enterprises in their full extent, which characterises the human condition. It is natural, and in this case it is right. What is natural here is to be valued over the artificial constructs of society and convention, which have stifled the Will to Power that naturally exists within us, or Schopenhauer’s misconstrued interpretations of the said will.

Most importantly, with this drive accounted for, I cannot prescribe what your something more will be. Indeed there is no merit in the ‘end’ itself, the merit of authenticity rather lies in the process of discovery and transcendence, and an embrace of these primal drives within us.

It is a truth I cannot prescribe nor enforce, and would not if I could. Instead, your journey is one to be driven entirely by self discovery. First, you must recognise and embrace the paradoxes of our reality, which surpass the comprehension of all men. Perhaps it is the value of our life that lies in this incomprehensibility; the great unknown, defiant of logic and reason, compels us to want life.

Your life will be determined to an extent by circumstances of fate; your family, place of birth, intelligence, appearance etc. All of these collude to form a parameter to your existence. These will shape how you are perceived in the world, and how you perceive yourself. And yet, it is within these deterministic bounds that you must utilize Nietzsche’s Will to Power, your free will, in the hope of one day breaking free of the dictates of your circumstances that deign you to be something that may be wholly incongruent to who you are as a person. Transcending these seemingly undeniable boundaries is remarkably similar to the experience of birth, which you are soon to be subjected to. The process of unveiling the truth or the reality previously kept from us is an abrupt moment of dislocation from your previous consciousness. Such a disruption is irreverent to the rhythmically reliable comforts of complacency and routine that society and Nietzsche’s “Herd” require for social functionality purposes.

Arthur Schopenhauer recognised the will that I have spoken about (terming it Will to Life), but instead of concluding as I have, aided by the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, that embracing the will was rational, he advocated that it was irrational, as the Will to Life in itself is a non-rational force, a blind, striving power whose operations are without purpose or design. Therefore any product resulting from an adoption of our Will to Life will be equally blind and meaningless. To Schopenhauer, life is a vacillation between two conditions: either pain, which is synonymous with drives and wants, or boredom. When we are not in pain, through our drives and wants, we are bored with the mundane triviality of our existence. We are propelled inevitably between the two poles, as each is considered uncomfortable and unhappy. Thus the universal condition of humanity is unhappiness. His ultimate conclusion is that one can have a tolerable life not by complete elimination of desire, since this would lead to boredom, but by becoming a detached observer of one's own will and being constantly aware that most of one's desires will remain unfulfilled.

This can be considered true of the “Herd” as Nietzsche would describe them in our cultural context. As a society, we have never been more dissatisfied with our lives. Is it a coincidence that this emotional and spiritual stagnancy has coincided with a period of history that has seen the greatest provision of material goods and services, that are supposed to make for our comfortability, than ever before in history? The things we surround ourselves with are designed to liberate us from toil, from Schopenhauer’s “want” or “pain”. They have done so successfully. At what cost, however? What we have seen is that they have anaesthetised us into a state of comfortability and boredom, further depriving us of the riches of the soul that the vagaries of struggle, toil, and experience are able to render within us.

Furthermore, Schopenhauer acknowledged that within the Will to Life was the powerfully significant force of the sex drive within us. Our conscious selves are merely a projection of these deep and underling forces within.

Indeed, it is conformity to the dictates of the will that results in more unhappiness, thus perpetuating our eternal condition.

The relative good life for Schopenhauer lies in suppressing and ignoring this blinding Will to Life. There is an underlying stoicism in his philosophy, where he simply accepts our state of existence for what it is. In Schopenhauer’s work ‘The Basis of Morality’, he tells us that ‘the difference of characters is innate and ineradicable.’ Thus, we are unable to change the nature we are born with. The determinism of the Will dictates our character, and thus by extension, governs the fortunes or misfortunes of our lives.

In today’s cultural context, we are too conditioned to accept this as fact, and thus we accept the inevitability of our own mediocre existence. We use the externalities that initially shape us as justifications for everything that is not according to our warped perception of what is ‘extraordinary’ in our lives. We have lost touch with that innate drive within us that screams out for the process of striving for something more. It shouts out to break the concocted societal mould that binds us within a shell of mediocrity, safety, and security; but it is silenced by the soothing call of material comforts.

In our celebration of superficiality, we have neglected that the path to an authentic existence, a path to fulfilling one’s humanity, lies within with our Will to Power. Instead, we idolise and objectify celebrities; we raise them above us as heroes, as definitions for Nietzsche’s higher man (Ubermensch), and thus create an impenetrable barrier between us and what is in any case a false perception of a flourishing human being.

The difference between Schopenhauer and Nietzsche’s philosophies lies in their conviction to their wants, drives, urges and impulses. While Schopenhauer’s stoic man accepts that life is imbued with unhappiness, and that his desires will go unfulfilled, and thus our wants are not worth suffering for. He consequently resorts to boredom, and maintains the status quo. Nietzsche’s man, on the other hand, values life, rather than resents it, and as a consequence of understanding that pain and suffering are a process vital to the securing of authenticity and truth, perseveres with what is considered unpleasant. Nietzsche is positively life affirming in his advocation that we take creative command of our drives, forces and impulses. We must become commanders and sublimators of our Will to Power, rather than subjects to the nihilistic misanthropy of the Will to Life.

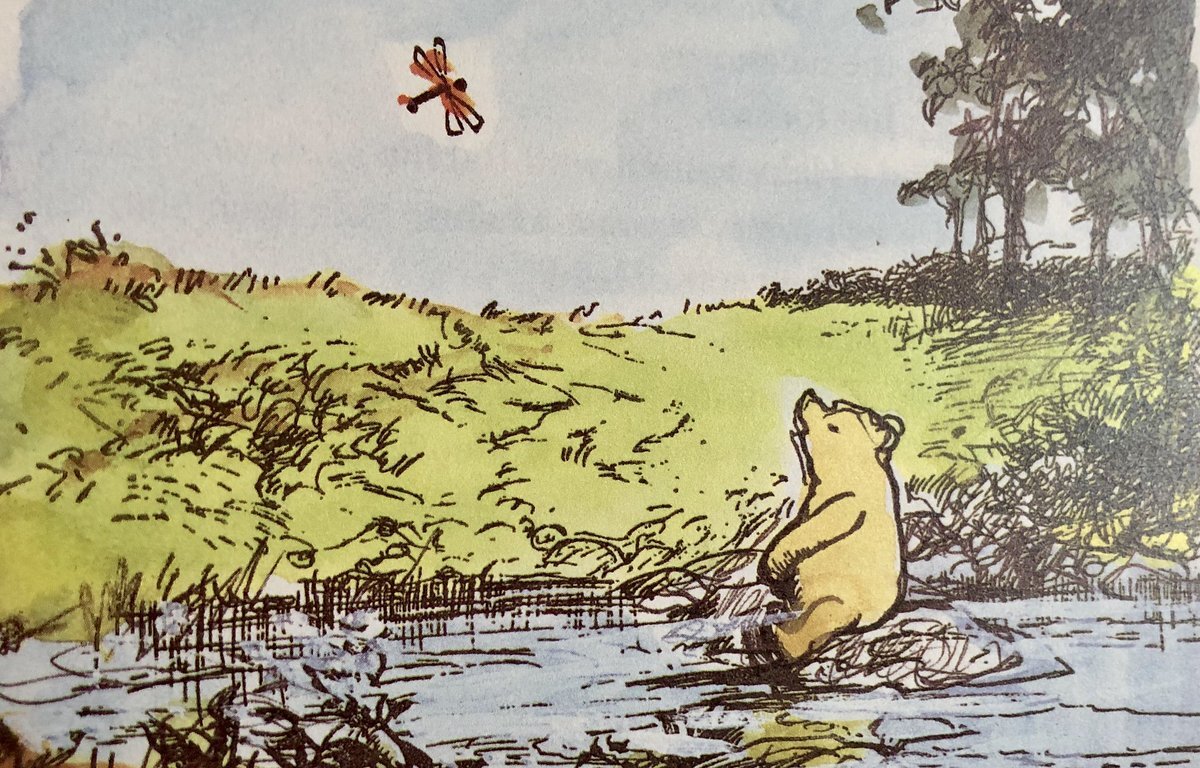

Despite this advocation of individual authenticity, which has been established to lead to a level of loneliness against the complacent, stoical mob, or Nietzsche’s ‘Herd’, I would like to advocate a seemingly counter-intuitive factor of our existence that at once seems to compromise the first securing of authenticity. Indeed it is our sociality and conviviality that is the second overarching factor of our dual nature and existence. This, combined with the adoption of our innate drives, compels us to arrive at another paradox of our existence. We are condemned to loneliness if authentic, yet cast into another level of inauthenticity if we deny the social nature of humanity.

There is great magic and joy to be found in interaction with other people, what Nietzsche describes as “the Herd”. Your spiritual salvation should not come at the price of loneliness or mocking from others, like Zarathustra. Knowing oneself is an entirely internal thing. Here is a line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “if”.

“If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings – nor lose the common touch…

You’ll be a man, my son.”

The path ahead of you, should you choose to embark upon such a quest for authenticity and truth, is not an easy one. Again, to quote Kipling, it is a matter of filling the “unforgiving minute with 60 seconds worth of distance run”. The process of this path of transcendence and discovery is of immense value in itself, namely for the depth of understanding it provides one of humanity, and also for the fact that it is congruent with who we naturally are as humans. Any end, which is not to be determined by anyone else other than yourself, is immaterial to the real gain you have attained, that of being a free spirit.