Written by the late Bob Ellis on his Table Talk blog, republished with permission from Anne Brooksbank.

***

Bob Carr implored me to see The Great Beauty and I did so with my wife at Norton Street yesterday. Afterwards I rang him suggesting it might be the best film ever made and he agreed. I said it was the greatest gift which in forty years of acquaintance and friendship he had accorded me. Let me explain.

A man like Marcello in La Dolce Vita has turned 65, and a flamboyant party occurs on the roof of his apartment which overlooks the Coliseum. The vigorous dances and aged faces, one a female dwarf, put one in mind of Hieronymous Bosch or the bright young things of Waugh's Vile Bodies, grown old. Hung-over, the birthday boy, Jep Gambardella, a literary journalist and courtier longtime of the decayed, once-glamorous aristocracy (he resembles Taki, Swann, Charles Ryder and Petronius), recalls the course of his life and the one good novel he wrote, still praised across Europe, forty years ago and why he did not attempt another.

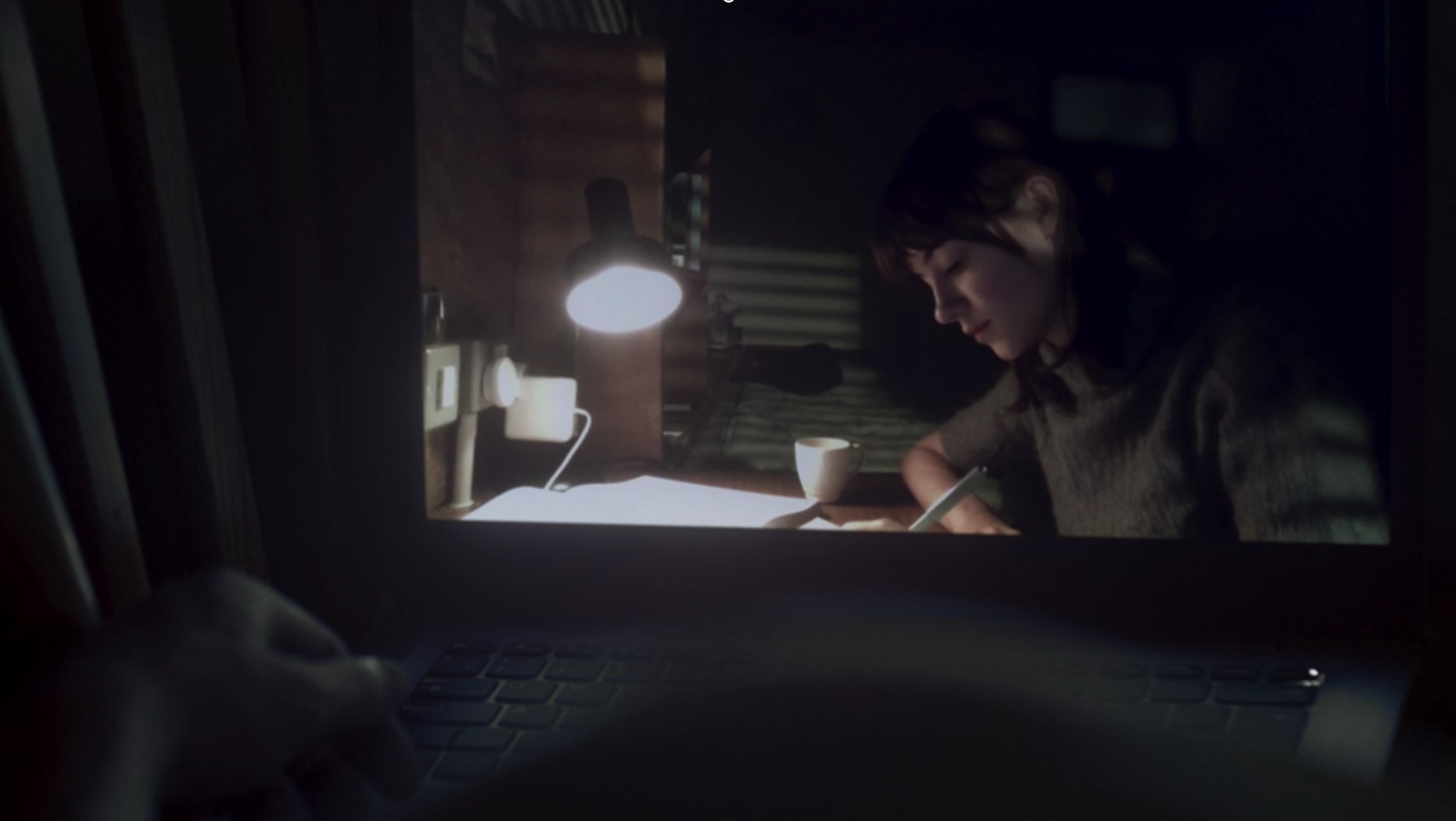

He goes in the following days to Eurotrash parties, intellectual dinner parties, garden parties, eccentric, explosive dance events and grimy strip-shows, meets a future Pope with lizard features famed for his exorcisms, tries to interview a toothless female deep-wrinkled Saint who, at 103, has never yet allowed herself a day's pleasure, watches a frenzied young girl action-paint a huge pointless mural, sobbing, before an awed celebrity audience, observes an outdoor 'artistic' event by a nude Marxist who bashes her bleeding head against a Roman viaduct, rehearses his commiserations at an important funeral, and so on. For a while he pursues a non-sexual relationship with Ramona, a badly facelifted stripper now 42 and slowly drugging and meditating herself to death but he cannot save her; and he confronts, at last, the memory of his dead first love, the subject perhaps of his second novel, which he starts, perhaps, at film's end.

This, though impressive, gives no great sense of the calm, exuberant beauty of the images that attend this narrative, lusher and sweeter and sadder than Fellini's Roma, or Antonioni's La Notte, or Visconti's The Leopard, as Luca Bigazzi's camera, soaring and swooping and sauntering, drifts past three thousand years of nocturnal statuary and architecture, not always crumbling, that still give meaning to hundreds, thousands, of autumnal, pretentious, briskly fornicating lives.

Wisely, Jep, the thoughtful narrating essayist-historian, fornicates only once himself, with a fiftyish old friend who apologises for her performance, and he has no lacerating ex-wives or difficult daughters to arbitrate and subdue. He drifts, like a ghost or attendant eunuch, with rehearsed compassion, calm eyes and the odd devastating soliloquy, through the lives of others: his elderly dwarf editrix; his junkie strip-club-owning friend whose daughter, Ramona, prefers to keep stripping – brilliantly – at 42 and squander, somewhere, her money; a female friend whose handsome crazy son appears as a red-stained nude Christ in public places, and is, she says, 'improving'; all these figures whom Waugh would present in flashes of lightning, scornfully, are here shown with tenderness and, though judged curtly sometimes, well understood.

Jep's first love is dead, lately dead, and her sombre widower reveals that she loved him, Jep, all her life and said so in a padlocked diary that he, the widower, read and in despair destroyed; so much is vanishing, like Rome's magnificence, as we watch. And Sorrentino, like others – Hawthorne, Henry James, Gore Vidal, Robert Hughes – lovingly watches it go, and sets down what he can. In the film's most remarked sequence, a young man with a walking cane and a key takes Jep and his non-mistress on a tour by night of Rome's most esteemed surviving busts and statues and bas-reliefs, dimly lit, in what seems like a dream, approaching death, of all of history's past achievement. In another we see on a sandstone quadrangle a hundred thousand tiny photos, maybe more, of the same man growing, day by day, from childhood to middle age.

It's a film, in short, that sums up so much of life that it would be good, I think, to show it at a weekend party that preceded one's self-euthanasia. It reminds us of how much of our happiness derives from being around good architecture; how dancing is an unmixed good; how the Italian spirit, from Rosselini, De Sica, Capra and Minnelli to Scorsese, Coppola and Tornatore is an exultant, pagan fount of hope that outruns in its pursuit of happiness all other civilisations; that we waste many, many days of our lives not being in Rome. And it tells us too how death comes, and the grace with which we receive it on that day and the days before is worth rehearsing.

In most American films the surgically altered faces are beautiful, or show past beauty. In films like this we see decay and wrinkling sadness garishly lipsticked and painted – and, in one scary sequence, botoxed – at every turn. We are reminded of beauty's brevity; and, in a great sense, of its irrelevance. So much of our lives is the pursuit of points of pride and ego, of public acclaim, when beauty goes. Fanny Ardant hurries past in moonlight looking much like Bronwyn Bishop and we see, alas, what Sorrentino mourns of what is past, and passing, and to come.

I could write many days on this film and perhaps I will. In the meantime, see it. See it; please.